Prostate cancer detection

PSA – measurable by standard blood test

Producing seminal fluid, the prostate also generates a molecule known as Prostate-Specific Antigen, or PSA. It is a prostate specific substance that circulates in the prostate and blood (concentration a million times lower in blood than in prostate). PSA is a tumor marker used at all stages of prostate cancer treatment: screening, diagnosis, post-treatment follow-up, diagnosis after recurrence.

PSA tests are often recommended from about age 50. Dosage is done with a standard blood test for which it is not necessary to be fasting. 8 days must separate PSA dosage from a rectal examination and 2 months in case of a recent rectal examination. However, PSA is not specific to prostate cancer because it also increases with other prostate pathologies: Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, inflammation and infection of the prostate. One of the first steps of prostate cancer diagnosis, PSA test must be completed by other diagnostics: 5 to 10% of cancers that can be felt during a rectal examination have a normal PSA at the start.

- Threshold value used for prostate cancer screening is 4 ng/mL: from 4 to 10 ng/mL, 70% of diagnosed cancers are localized.

- A PSA higher than 30 ng/mL reflects an advanced localized prostate cancer with a high probability of locoregional lymph node metastases.

- A PSA higher than 100 ng/mL reflects an advanced localized prostate cancer, with a high bone metastases probability.

Sources:

(1) Les traitements du cancer de la prostate, collection Guides patients Cancer Info, INCa, novembre 2010

(2) La prise en charge du cancer de la prostate. Guide patient – Affectation de longue durée, HAS, juin 2010

(3) L’antigène spécifique de la prostate ou PSA, Prog Urol, 2011, 21, 11, 798-800, R. Boissier (www.urofrance.org)

Digital rectal examination

This examination is performed by a general practitioner during a normal consultation. The physician inserts a finger into the patient’s rectum in order to feel the prostate. This is a quick, painless procedure.

Prostate biopsies

To determine whether a patient is suffering from prostate cancer, a biopsy is performed. This involves removing tiny fragments of prostate that are then analysed in the laboratory in order to study the types of cell contained in the samples. Before examination is performed, patient is given an enema (washing out the rectum with a liquid solution) and an antibiotic treatment. Under local anesthesia, guided by an ultrasound scanner (with a probe inserted into the rectum) that produces an image of the prostate, the physician collects at least 12 tissue fragments from different parts of the prostate. They are then examined under the microscope by an anatomopathologist who will confirm or not the presence of a cancer. Its objectives are:

- Specify aggressiveness of the cancer cells defined according to a scale called Gleason score (degree of differentiation of the tumor, ie the tendency of the tumor to resemble a normal tissue of the prostate),

- Evaluate number and distribution of positive biopsies (showing cancer cells), characteristics of the tumor tissue and the crossing of the cancer cells beyond the prostate capsule.

Gleason score

Gleason Score is THE prostate cancer prognosis factor. Prostatic tissues contain several components: a glandular tissue, a smooth muscular tissue and a stromal tissue (extracellular environment).

Gleason score defines prostate cancer at an architectural level. Score is based on 3 rules:

- within the prostate, several categories of tumor cells possible

- these tumor cells may have different grades

- the more the gland architecture is destroyed, the worse the prognosis

After biopsies analysis, when several tumor cells are different from the gland, Gleason score is then the sum of the two tumor cells group. It starts from 2 (1+1), written 1-1, to 10 (5+5) written 5-5. Redefined in 2005, Gleason Score no longer consists of only 3 grades, from 3 to 5. Therefore, it extends, in case of different tumor cells group from 3-3 (6) to 5-5 (10).

Gleason Score characterize tumor aggressiveness:

- Gleason Score 6 (3–3): undifferentiated and mildly aggressive tumors

- Gleason

Score 7 (3–4 or 4–3) : moderately differentiated tumors

- In this category, Gleason Score tumors 4–3 are more aggressive than tumors which have a 3–4 score

- From Gleason 7 score, we speak of adenocarcinoma of the prostate, the tumors studied being revealed malignant.

- Gleason Score 8–9–10: very undifferentiated and very aggressive tumors

Source:

Le score de Gleason pour les nuls, Progrès FMC, 2014, 24, 1, F13-F15, L. Salomon (www.urofrance.org)

“Amico” classification

Before treatment, the Gleason score, associated with the clinical stage and the PSA level, makes it possible to define a so-called Amico classification allowing to distinguish:

- Low risk tumor (Clinical T1c or T2a, PSA level <10ngr/mL and Gleason Score 6) ;

- Middle risk tumor (Clinical T2b or T2c, PSA level from 10 to 20ngr/mL and Gleason Score 7) ;

- High-risk tumor (Clinical T3, PSA level >20ngr/mL and Gleason Score >7).

It is from these elements supplemented possibly by the results of a radiological extension assessment that the therapeutic strategy will be defined.

Source:

Le score de Gleason pour les nuls, Progrès FMC, 2014, 24, 1, F13-F15, L. Salomon (www.urofrance.org)

Staging

Once a prostate cancer is diagnosed, the diagnostic must be completed by an imaging examination series. This assessment will make it possible to define precisely whether the cancer is localized to the gland or whether it is extensive.

Scan

This painless examination, which lasts between 10 and 15 minutes, uses X-rays to produce a very accurate image of the target area, in this case the abdomen and groin (abdominopelvic scan). The scan will reveal whether the prostate cancer has remained within the gland or has instead reached the prostatic capsule (i.e. the membrane surrounding the prostate), the lymph nodes.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Before the examination, a rectal preparation is essential to have a rectal vacuity, an antispasmodic injection may be recommended. Examination is painless and last from 30 to 40 minutes. After a medical questionnaire, the patient is taken to an examination room where he will have to remove all his metalic objects and put on a white coat. The patient is then installed in a supine position; an external antenna and / or an endo-rectal antenna are installed. In some cases, a liquid contrast agent must be injected via a venous access. The patient is then introduced into the central area of the MRI that looks like a tunnel. The X-ray technician will then communicate instructions to the patient by a microphone. The patient will hold an alarm in his hand that he can activate in case of problems.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) looks like a scanner. It use body cells reaction subjected to a magnetic field and transform this response into images. It distinguishes soft, healthy and abnormal tissues. Prostate MRI allows the anatomical and functional study of the prostate gland thanks to the strong contrast of soft tissues composing the gland and the diagnosis retranscription on high-definition images. MRI can detect clinically significant lesions and will mainly determine the treatment strategy to adopt according to the cancer type diagnosed.

Source:

Imagerie du cancer de la prostate: IRM et imagerie nucléaire, Prog Urol, 2015, 25, 15, 933-946, R. Renard-Penna (www.urofrance.org)

Bone scintigraphy (bone scan)

This examination can detect the spreading of prostate cancer to the bones. It consists in injecting a slightly radioactive product into the body that will bind on areas with high bone metabolic activity (tumors and bone metastases are clumps of cells that divide fastly and uncontrollably).

- The patient receives an intravenous isotope that will bind to abnormally active masses (tumors and bone metastases).

- The patient is then lying on the table and passes through a tube that contains a series of sensors sensitive to the radioactive radiation of the isotope.

- The bones and parts of bone suspected of being affected are viewed; the final images are then reconstructed.

The entire skeleton is observed in a single examination that lasts, preparation not included, about 50 minutes.

Source:

La scintigraphie osseuse, Fondation contre le cancer (www.cancer.be)

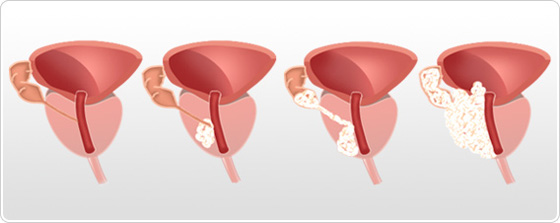

Prostate cancer different stages

The quantity of cancer present in the body and its location at diagnosis time determines the stage of prostate cancer. Screening exams (described above) also determine the tumor size, the parts of the organ affected by cancer and its extent (localized or spread cancer outside the prostate capsule).

Classification named « TNM » is the staging system the most used to classify prostate cancer as follows four stages (T1, T2, T3 et T4).

Cancer staging will help determine the treatment strategy to implement.

Prostate cancer stage 1 and 2 ( T1, T2): Localized cancer

Prostate cancer stage 1 (T1)

The tumor is not palpable in digital rectal examination. Only a few cells are cancerous. Patient has no symptoms of the disease.

- T1a : tumor in less than 5% of resected tissue

- T1b : tumor in more than 5% of resected tissue

- T1c : tumor discovered with prostate biopsy after observing a rise in PSA rate

Prostate cancer stage 2 (T2)

Tumor is palpable by rectal examination (presence of a hard mass) and seems to be localized to the prostate gland.

- T2a : tumor reaching half a lobe or less

- T2b : tumor reaching more than half a lobe but not reaching the 2 lobes

- T2c : tumor reaching the 2 lobes

Prostate cancer stage 3 and 4 : Advanced cancers

Prostate cancer stage 3 (T3)

The cancer has spread out of the prostate gland and/or to seminal vesicles.

- T3a : cancer extension outside the prostate capsule

- T3b : cancer extension to seminal vesicles

Prostate cancer stage 4 (T4)

Nearby organs of the prostate (bladder, rectum, and sphincter) has been invaded by cancer.

Sources:

(1) Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK and Wittekind C (eds.). (2017). TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. (8th Édition). Wiley Blackwell.

(2) Djavan B, Bostanci Y, Kazzazi A. Epidemiology, screening, pathology and pathogenesis. Nargund VH, Raghavan D, Sandler HM (eds.). (2015). Urological Oncology. Springer. 39: 677-695.

(3) National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer (Version 1.2016). Extrait de: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf